Test instrumentation can be expensive, and one effective way to reduce that cost is with switching. In the sections below, I’ll walk through a few real-world examples of switching architectures I’ve relied on over the years to help customers improve their test systems.

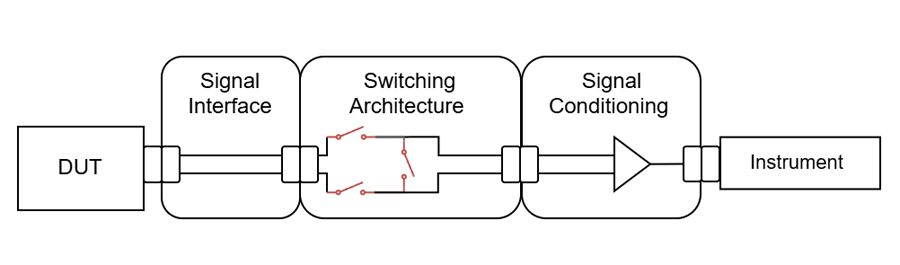

A typical automated test system has several layers: The first is the interface to the device under test (DUT), which adapts the test system’s connections to the DUT’s specific form factor. Then there’s the signal conditioning layer, which adjusts instrumentation signal levels to match those required by the DUT. After that, there’s the instrumentation layer itself, responsible for generating or measuring signals such as digital I/O, analog I/O, communication buses, power buses, or arbitrary waveforms.

Finally, there’s the switching architecture layer, which routes signals from the instruments out to the DUT. This layer is the focus of this discussion.

The switching layer plays a critical role in both reducing cost and improving flexibility. It can dramatically reduce the amount of instrumentation hardware required while allowing the test system to maintain a common test interface that automatically reconfigures itself for multiple DUT variants. Switching can also improve throughput, enabling parallel testing of multiple units or rapid reconfiguration between tests.

In addition, a well-designed switching architecture can give development engineers deeper insight into their systems by allowing many test points to be accessed by a shared set of instruments.

Basic Switching Blocks

Before diving into specific switching architectures, it’s helpful to review two fundamental building blocks that form the basis of most switching systems: the switch matrix and the multiplexer (mux).

Switch Matrix

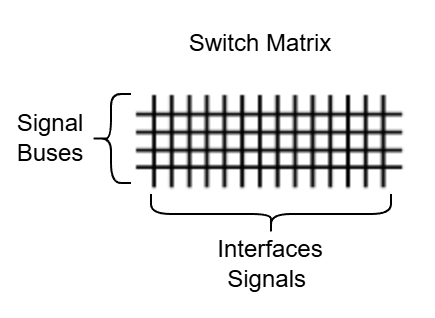

The first building block is the switch matrix. You can find a more detailed discussion of switch matrices in this post, but in general, a switch matrix can be thought of as a many-to-many connection block. It allows any signal present on its interface to connect to any other signal on the same interface.

Switch matrices are typically characterized by two main features:

- Number of signal interfaces: how many individual signals can connect into the matrix.

- Number of signal buses: how many common signal lines those interfaces can be routed onto.

Matrices are often described using these dimensions. For example, the “14×4 matrix” shown below provides 14 interface signals (represented by the vertical lines) and 4 signal buses (represented by the horizontal lines), allowing flexible interconnection between multiple instruments and DUT channels.

Multiplexer

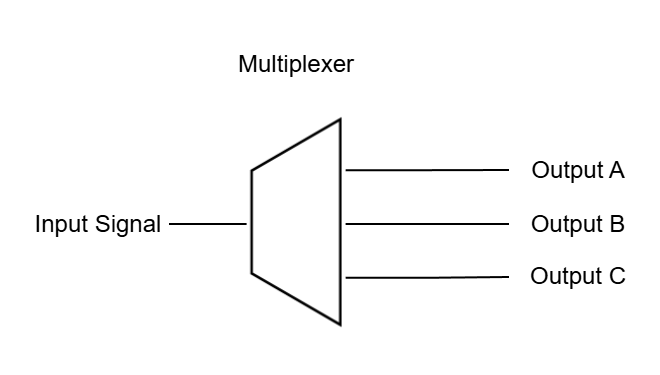

The second fundamental building block is the multiplexer, or mux. A multiplexer provides a one-to-many or one-of-many connection path.

For this discussion, there are three specifications to pay attention to:

- Channels: the number of output paths the input can be connected to.

- Banks: groups of channels that can be switched independently.

- Poles: the number of conductors switched together (for example, a single-pole or double-pole mux).

A simple example is a three-channel, single-pole, single-bank mux, which allows a single input signal to connect to any one of three output channels.

It’s important to note that not all multiplexers behave the same way. Some allow the input to connect to more than one output simultaneously, while others restrict it to a single output. For the purpose of this article, we’ll assume a multiplexer can connect a signal to none, one, or more than one output channel, depending on design.

Other Basic Blocks

To help illustrate the switching architectures discussed later, the following schematic symbols will be used.

Real World Architectures

A Simple Switch Matrix

Use Case

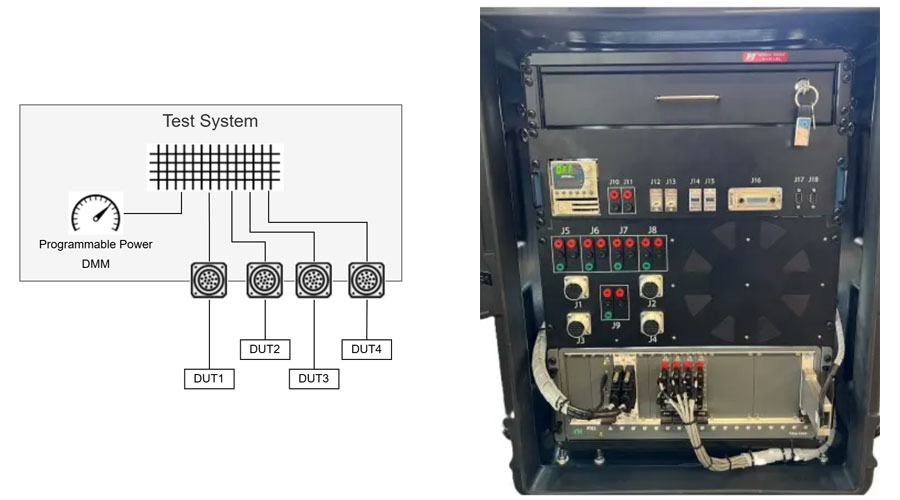

This is one of the simplest and most straightforward switching architectures, but also one of the most common and powerful. It forms the foundation for DMC’s Helix SwitchCore platform and served as the base architecture for a Mobile Calibration Test Stand (MCTS).

Despite its simplicity, this design provides a great balance of flexibility, scalability, and maintainability, making it ideal for systems that need to test multiple variants of a product or perform parallel testing.

Switching Architecture

In this architecture, DUT signals and instrument signals share the same switch matrix. The matrix is selected to provide the appropriate number of buses and interface connections based on the test requirements.

For example, the MCTS system implemented a 64×12 switch matrix, providing:

- 64 interface signals to accommodate multiple DUT configurations, and

- 12 signal buses for routing measurement and power signals across multiple devices.

The system included multiple digital multimeters (DMMs) and programmable power supplies connected through the matrix. This setup allowed the system to test up to four DUTs simultaneously or quickly reconfigure itself to adapt to different DUT pinouts.

Architecture Benefits

- Simple: A single switch matrix handles the entire routing scheme, and no additional routing layers are required.

- Expandable: The initial system used a 64×12 matrix, but the design allows for expansion simply by adding additional matrix modules. DMC’s SwitchCore architecture can be expanded to support thousands of signals, as in this implementation.

- Configurable: Any instrument can be routed to any DUT pin, making it easy to add new instruments or modify DUT configurations without requiring a complete redesign of the test system.

Voltage Isolation Multiplexer

Use Case

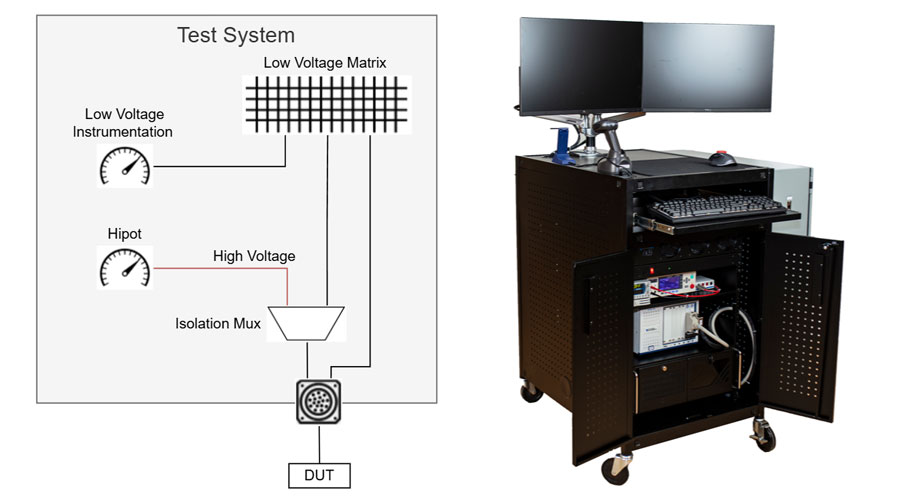

This architecture was used on a Power Distribution Unit (PDU) End-of-Line (EOL) Test System that supported testing for an entire family of power distribution units.

One of the required functional tests was a high-potential (hipot) test up to 700 VDC. However, several other tests on the same DUT pins required low-voltage instrumentation. To further complicate matters, the system also needed to support multiple product variants, each with different DUT pinouts and electrical specifications.

Switching Architecture

To meet these requirements, this switching architecture built upon the simple matrix design by adding a layer of high-voltage multiplexing.

The multiplexer layer enabled safe high-voltage testing—such as hipot tests—while maintaining the flexibility to route low-voltage signals to the same pins. It also provided isolation between high- and low-voltage paths, protecting sensitive instruments during high-voltage operation.

From a cost perspective, the flexibility of the matrix was critical. Rather than multiplexing every signal line, only the 12 DUT pins requiring high-voltage capability were routed through the high-voltage mux. The remaining 24 signals connected directly to the matrix. This selective approach reduced hardware costs by limiting expensive high voltage switching components to only the lines where they were needed, without sacrificing system adaptability.

In this configuration:

- The DUT signals first passed through a high-voltage multiplexer with 12 banks of two channels each.

- The DUT interface supported up to 36 pins, with 12 routed through the high-voltage mux for hipot testing and the remaining 24 connected directly to the switch matrix.

This architecture preserved the reconfigurability of the base matrix design while adding high-voltage capability and cost efficiency—all within a single, unified system.

Architecture Benefits

- High-voltage isolation: Enables high-voltage testing functionality without sacrificing access to DUT pins for low-voltage measurements.

- Integrated hipot testing: Combines what are often two separate test stands (functional test and hipot test) into a single system, eliminating an extra manufacturing step and improving throughput.

- Cost-effective design: By routing only necessary lines through the high-voltage multiplexer, the design minimized the number of costly HV switching components required.

- Configurable and scalable: Maintains full flexibility to support multiple product variants and adapt to future test requirements.

Distributed Multiplexing for Single Point Measurements and Monitoring

Use Case

In development test systems, engineers often need the ability to probe various signals throughout a system during debugging or validation. This is commonly done using a handheld digital multimeter (DMM). However, as systems grow to include hundreds or thousands of signals, manual probing quickly becomes impractical, time-consuming, and error prone.

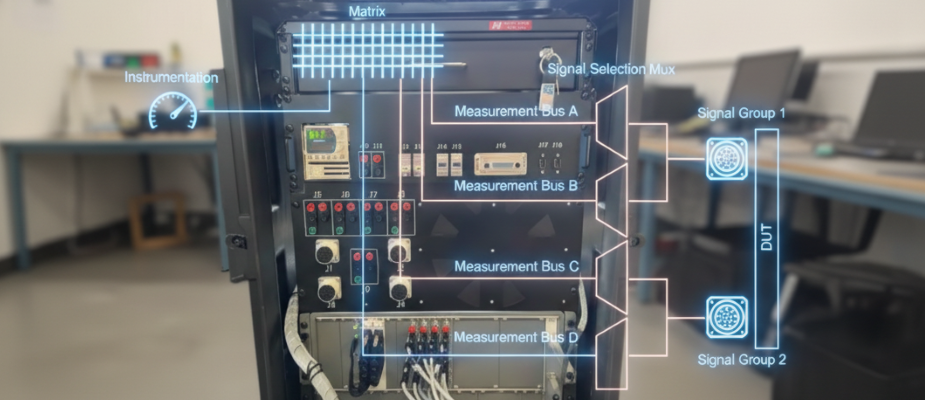

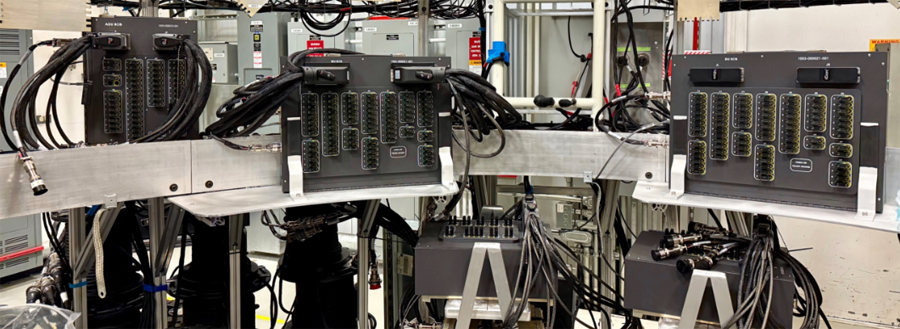

Hand probing also introduces risks: it can break configuration integrity or even violate procedural control requirements, particularly in aerospace and safety-critical applications. To address these challenges while maintaining flexibility and automation, a distributed multiplexing architecture can be implemented. We most recently leveraged this for a project using our Auto-BOB architecture.

Switching Architecture

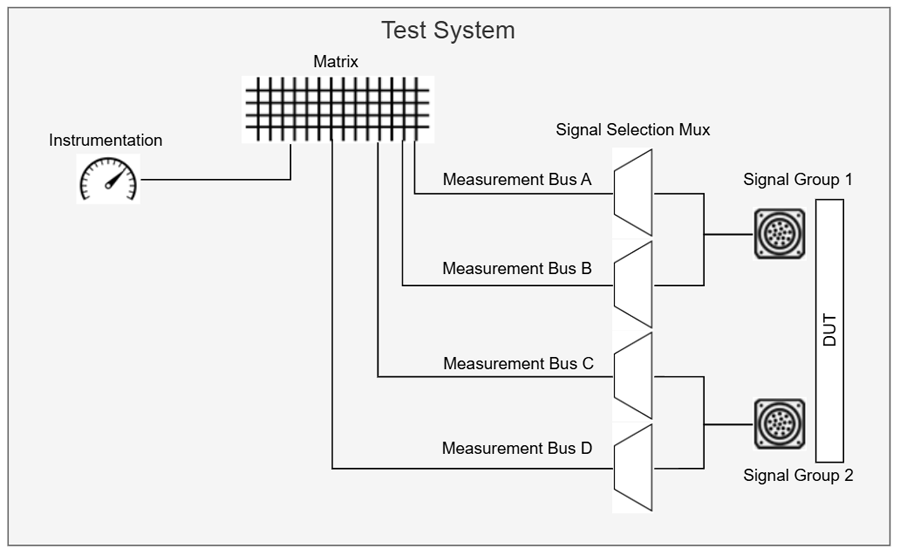

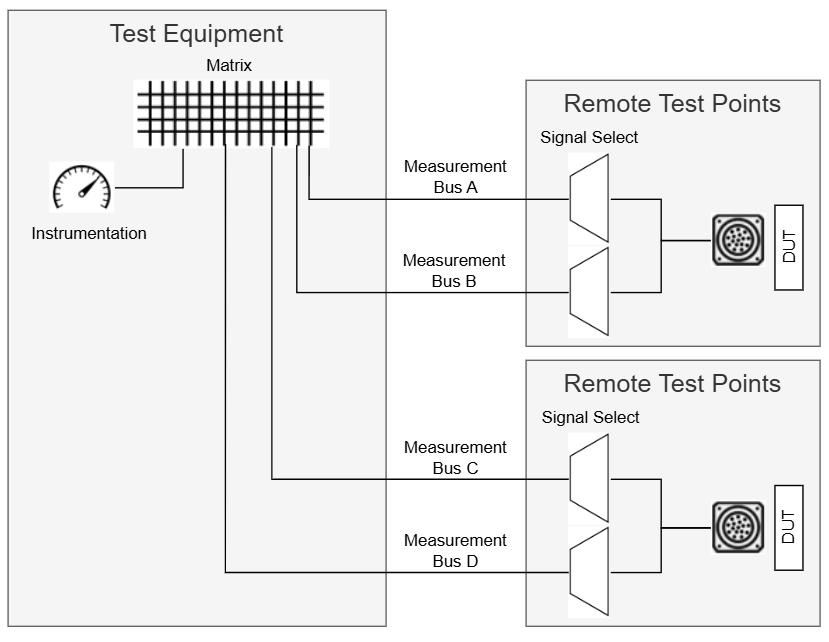

This is one of the most complex switching topologies, using a multilayered approach to balance flexibility, scalability, and cost.

While large switch matrices can provide ultimate routing freedom, they become expensive as channel count grows. By introducing layers of multiplexing, the system maintains the core configurability of a switch matrix but significantly reduces costs through signal down-selection using lower-cost multiplexers.

This approach pays off particularly for very high channel-count systems, where the total number of signals can reach hundreds or thousands.

To enhance reliability and safety, this architecture often employs specialized monitored multiplexers that can verify the switch position and ensure no inadvertent shorts occur within the system.

Each DUT signal passes through multiple multiplexers, with each multiplexer creating its own measurement bus. This effectively gives each DUT signal multiple probe or measurement points that can be dynamically routed to instrumentation. Only one signal can occupy a measurement bus at a time, but by distributing signals across several buses, engineers can measure any two points in the system through the shared switch matrix.

In one implementation, each signal group was tied to two measurement buses. For example:

- Measurement buses A and B serve Signal Group 1.

- Measurement buses C and D serve Signal Group 2.

Because each multiplexer handles multiple DUT signals, a single signal must connect to two separate multiplexers to enable pairwise measurement while maintaining isolation. These selected signals are then routed back to the switch matrix, which connects to all instrumentation (DMMs, power supplies, etc.).

An additional advantage of this design is its distributed nature. The multiplexers can be physically separated from the main switch matrix enclosure, with local multiplexers housed near DUT interfaces and the matrix located near shared instrumentation. This setup allows multiple test systems to share the same pool of measurement instruments, further reducing equipment cost and improving overall utilization.

Architecture Benefits

- Highly scalable: Supports systems with hundreds or thousands of signal channels without requiring massive monolithic switch matrices.

- Cost-efficient: Reduces high-density matrix requirements by layering lower-cost multiplexers for signal selection, minimizing total hardware expense.

- Flexible and configurable: Allows any two points in the system to be connected for measurement, supporting a wide range of development and diagnostic tests.

- Improved safety and reliability: Monitored multiplexers verify switch positions and prevent inadvertent shorts or misconfigurations.

- Distributed design: Enables instrumentation to be shared across multiple test systems, reducing overall equipment investment and maximizing utilization.

- Supports automation and repeatability: Eliminates the need for manual probing, improving consistency and compliance in regulated or high-complexity environments.

DUT Multiplexing for High Throughput End of Line Test

Use Case

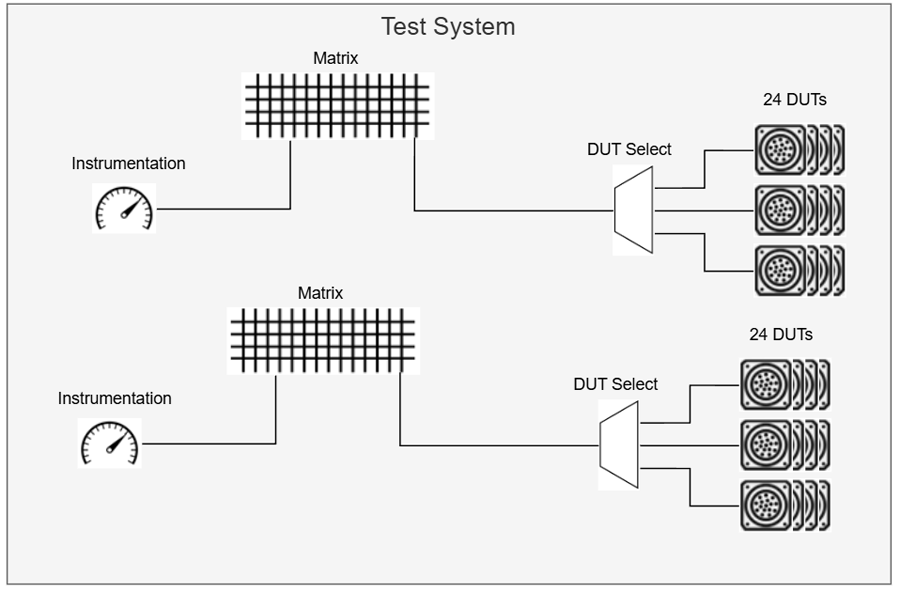

In a manufacturing environment, throughput matters. In DMC’s Automated Photodiode Tester Application, multiplexers and switch matrices were combined to enable batch testing of up to 48 devices under test (DUTs). Multiplexers cycled through each DUT to perform functional testing, while a shared switch matrix handled instrument routing. This combination allowed the system to test multiple DUT variants with different interfaces and specifications using a common hardware platform.

Switching Architecture

This system used a 24-channel, eight-pole multiplexing card to select one of 24 DUTs. Each DUT had eight pins, with each pin connected to a separate pole of the multiplexer. Because the multiplexer provided 24 channels with eight poles each, a single mux card could support up to 24 DUTs.

By adding a second identical card, the system expanded to 48 DUTs total. The outputs of the multiplexer cards were routed into a switch matrix, which connected to the functional test instrumentation.

To achieve higher throughput, duplicate instrumentation and matrix modules were added to the system, one for each multiplexer card, allowing the system to operate in parallel. This configuration enabled testing over 300 DUTs per hour, dramatically increasing production efficiency while maintaining flexibility across product variants.

Architecture Benefits

- High throughput: Parallelized multiplexing and shared instrumentation allowed testing of dozens of DUTs simultaneously, achieving over 300 units per hour.

- Scalable and modular: Additional multiplexer cards or matrix modules can be added to increase capacity or support new product families.

- Efficient use of instrumentation: Shared matrix routing maximizes the utilization of costly test hardware, minimizing total equipment investment.

Multiplexing for Differential Serial Bus Electrical Verification

Use Case

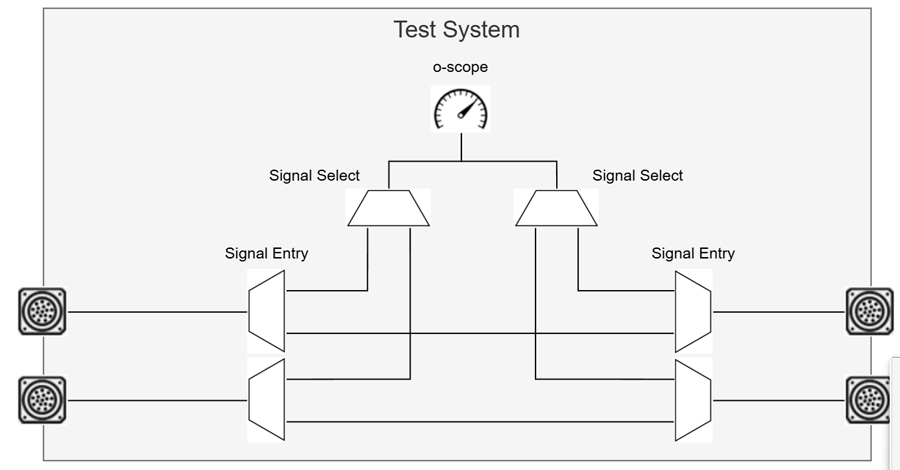

This is a niche but fascinating application of switching architecture. Integration engineers often verify data integrity on serial communication buses, but sometimes it’s also necessary to capture and analyze the electrical characteristics of the signal itself.

This poses unique challenges. Serial buses often operate at data rates exceeding 1 Mbps, where any additional loading, attenuation, or reflections introduced by the test system can degrade signal quality. In these cases, the test setup must be designed to minimize its electrical impact, because it’s the signal quality itself, not just the transmitted data, that’s under evaluation.

Architecture

Testing multiple serial buses compounds the difficulty. To address this, DMC implemented a stubless multiplexing architecture designed to preserve signal integrity while allowing automated electrical verification and waveform capture.

The system was constructed using several double-pole, double-throw (DPDT) relays, each acting as a two-channel, two-pole multiplexer. By chaining these relays in a tree configuration, the architecture could select any one of several serial buses to route to an oscilloscope for signal capture.

When a bus was not selected, its signal passed directly through the system without interruption, allowing all buses to continue normal communication. When a bus was selected, its signal was routed up to the oscilloscope while simultaneously passing through the test system and back out, enabling real-time monitoring without disrupting communication.

This design minimized the formation of stubs on the communication lines, which is critical for maintaining clean signal edges and preventing reflections that can corrupt high-speed signals.

Architecture Benefits

- Preserves signal integrity: The stubless relay topology minimizes reflections and loading, ensuring accurate electrical characterization of high-speed differential signals.

- Enables real-time testing: Signals can be captured while communication continues uninterrupted, allowing engineers to validate bus behavior under true operating conditions.

- Automates complex measurements: Multiplexed relay control allows seamless switching between buses for waveform capture, reducing manual reconnections and improving test throughput.

Conclusion

Switching architecture might not always be the flashiest part of a test system, but it’s often what determines how flexible, scalable, and future proof that system can be. From simple switch matrices to complex multi-layer multiplexing and distributed setups, each architecture offers a different balance of cost, capability, and control.

In development environments, flexibility can mean the difference between a day and a week of reconfiguration. In production, smart multiplexing can translate directly into higher throughput and lower test costs. And in specialized electrical verification setup, like high-speed serial bus testing, the right switching design can be the difference between reliable measurements and misleading results.

At the end of the day, the best architecture isn’t always the most complex: it’s the one that fits your goals, scales with your products, and keeps your test system adaptable for whatever comes next. Thoughtful switching design doesn’t just connect instruments and devices; it connects your entire test strategy to long-term success.

Ready to take your Test & Measurement project to the next level? Contact us today to learn more about our solutions and how we can help you achieve your goals.