Over the past few decades, there has been an explosion of suburbs in America: more people are dispersed across the country in more thinly populated communities.

Traditionally, rural areas handled utilities on a per-house basis with water wells and septic tanks; however, most new suburbs were built with full service water and wastewater systems handled by their cities. This resulted in utility providers handling utilities in larger areas with fewer people – and, therefore, smaller budgets.

Now, with over 50,000 utility providers across the country, many with aging pipes and control systems as well as ever shrinking budgets, cities are facing a new realm of cybersecurity.

The control systems for many utilities are increasingly networked, and some are even on the internet. Unauthorized access of these systems by bad actors is no longer a hypothetical — as we have seen by the hack in Oldsmar, Florida.

To combat this, the Federal EPA, along with the various state EPAs, have implemented new rules and regulations to encourage better cybersecurity practices. One such rule, specified in the American Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA), mandates that all water and wastewater utilities of a certain size perform a Cybersecurity Assessment.

DMC recently had the opportunity to perform one of these assessments for a municipal water/wastewater utility. In this article, we will share some of our generalized findings.

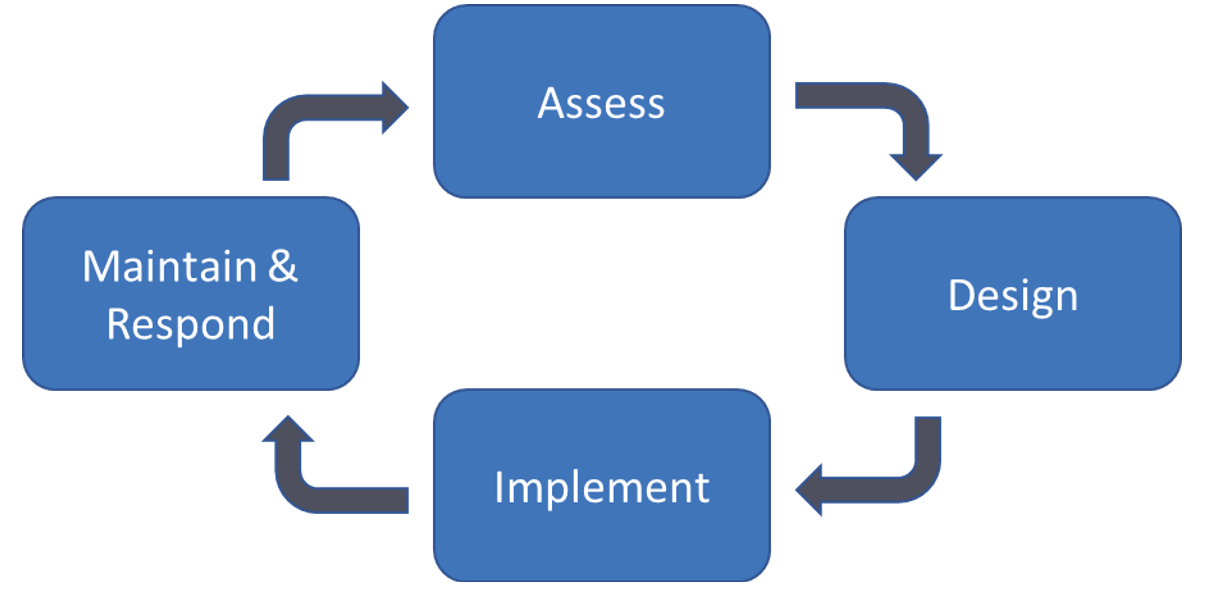

A cybersecurity assessment is the first step in the broader cybersecurity lifecycle. It is a process of uncovering the cybersecurity vulnerabilities in a system and rating the risks associated with those vulnerabilities.

There are many guides and resources available for the cybersecurity lifecycle and cybersecurity assessments: such as the ISA 62443 standard. While these guides and standards are applicable for numerous types of systems, it is still useful to understand some of the unique risks that water and wastewater control systems face.

- Critical Uptime

While most control system owners and operators would likely describe the uptime of their systems as critical, few systems have as much bearing on people’s lives as water and wastewater systems.

Unplanned downtime doesn’t just cost money, but it has the potential to affect the health and safety of hundreds to hundreds of thousands of people. This means that every vulnerability is likely to result in a much higher risk because the consequence of any bad act is so extreme.

Risk = Likelihood X Consequence.

It is nearly impossible to improve the cybersecurity of a system without understanding and rating its various risks. The formula above is a simple way of producing a numerical value for each risk by considering the likelihood and consequence of some action or exploit occurring.

- Vendor Reliance

Many water and wastewater systems are municipally run and funded. This often means that there may not be any Instrument and Electrical (I&E) or control systems specialized persons on staff. Rather, many of the systems are maintained by the vendors that installed them. There may even be multiple vendors maintaining different systems at a single plant.

For each different vendor solution, you must consider how the vendors will access their system for support, the interoperability of their system with others in the plant, and the long-term support potential.

- Geographically Disperse Locations

To provide services across an entire community, water and wastewater operations must have controls equipment miles or even dozens of miles apart. Between the water towers, pump stations, lift stations, treatment plants, offices, and meters, there may be controls equipment dozens of miles away from the main operating centers.

This not only leads to a larger attack surface but increases the amount of time and resources it takes to secure all the sites. This often results in an architecture using the internet to connect all of these locations together: which adds extra risk not present in systems with a single private network.

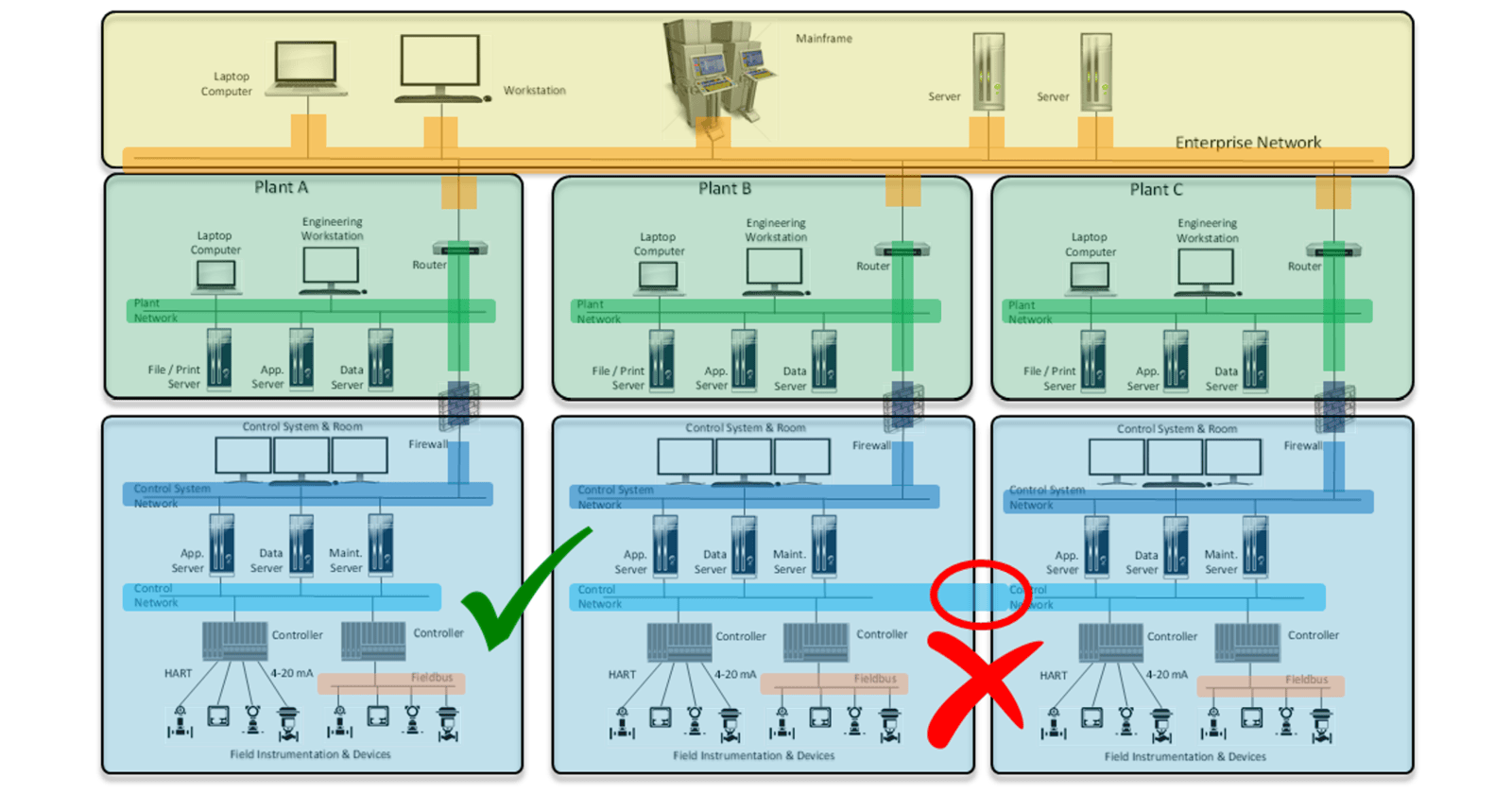

The Zone and Conduit Model is a method of breaking up systems by their security level and connection to other levels.

Grouping objects into similar security zones and identifying their conduits of information to the other zones can help to simplify the security of complex networks of machines and systems.

Checkout this blog by the National Cybersecurity Institute of Spain for more information on the Zone and Conduit Model.

There are common sense steps to securing a control system that likely make sense across the spectrum. For example, the US Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has a number of recommendations available that provide a great place for any control system owner or operator to start (https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ics/Recommended-Practices). Below are some of the recommendations that we have found to be especially relevant to water and waste water utilities.

- Remove all remote access software from SCADA/Controls PC’s immediately.

- We understand some of these PCs may also serve as an office computer, but we recommend at least removing Zoom, Teams, TeamViewer, and any other remote access applications from these PCs. Ideally SCADA and Controls PC’s would only run applications necessary to their controls functions, and all office, email, or time management applications would be run on a separate machine.

- Keep track of all vendor/3rd party access to your system.

- Ensure that you understand if and how your vendor gets access to their system if they need to support it. Ideally, support would come from an in-person technician, but that may not always be feasible for time or budgetary reasons. If remote support is necessary, make sure you have a full understanding of where and how this access is granted. Request that any passwords used for access are secure and unique to your plant and discuss with the vendor the possibility of unplugging any gateways or modems used for remote access when not in use.

- Segregate your office and controls networks.

- The fewer devices you have on your controls network, the more secure your system will be. Ideally you would only have the bare minimum devices required to carry out your systems function (e.g. PLCs, HMIs, SCADA PCs, Flow Computers, etc.) and all other office computers, phones, or security cameras would be on a completely separate network. As many systems increasingly need the internet to function, you may not be able to completely air gap your controls and enterprise networks. In these cases, we recommend using your router or managed switches to create VLANs to virtually separate these networks.

- Lock down and monitor all sites.

- A physical attack may not always come in the form of an armored vehicle or an agent with a USB drive hidden in their shoe. Anyone could cause just as much damage if given unmitigated access to certain systems. For remote sites, consider implementing security cameras to monitor the access points or equipment. For plants or operations centers where staff may be moving around throughout their shifts, consider keycard systems to ensure the doors are locked at all times but personnel are not inhibited from carrying out their jobs.

- Maintain backups of all programs and mission critical data and consider backup hardware.

- Even without a cyber-attack, it is not uncommon for hard drives to fail or PLCs to short. For all of your controllers and PCs, consider how you would resume operations if that device or software were to fail. Consider creating PC images of your SCADA computers and keeping backups of PLC programs. If you rely on vendors for this equipment, request that your vendor keep secure backups and potentially even keep a copy at your site. Ideally you would follow Peter Krogh’s “3-2-1” rule for backups which is to keep “3 backups on 2 different types of media and at least 1 offsite”.

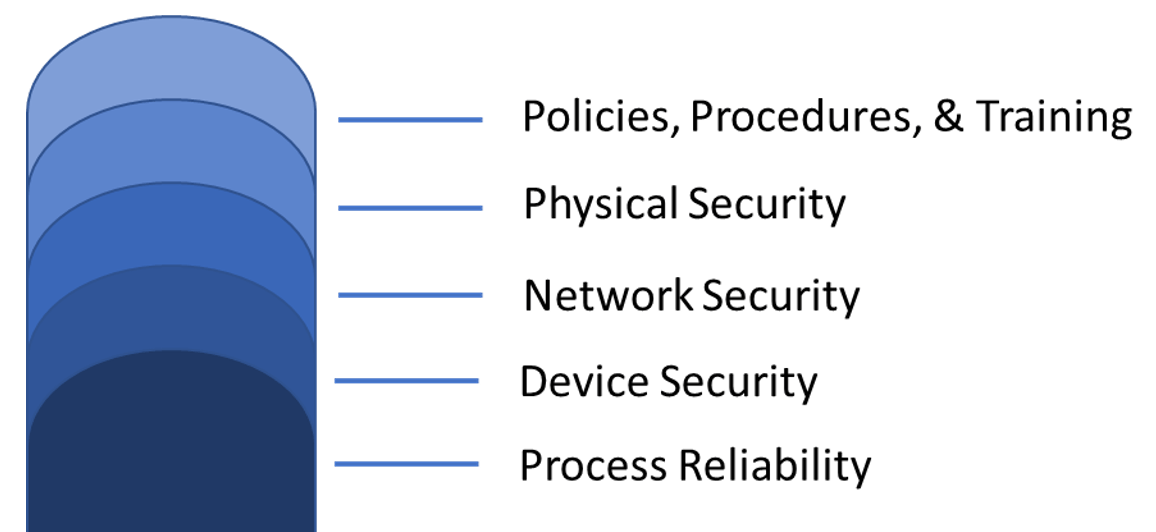

Cybersecurity is best achieved using an approach of layered protection. No mitigation or security measure is perfect, but when multiple different forms of protection are layered on top of each other, you can be more assured that one of the layers will impede an attack.

Water and wastewater systems in the US are in a unique position of being major targets of cyber-attacks, but they are often lacking the resources to implement major cybersecurity measures. Thankfully, federal and state agencies across the country have taken notice, and, through efforts like those outlined in AWIA, measures are now being taken to secure these systems and educate the owners and operators on good cyber hygiene.

Ultimately, all control systems are different and will have different needs. The risks and recommendations mentioned here may not make sense for all control systems or even all water and wastewater systems, but cybersecurity is an effort of continuous improvement. Hopefully some of the risks and recommendations in this article will provide insight into your own system and will motivate you to take the initial steps of improving the cybersecurity of your system.

If you are looking to have a cybersecurity assessment performed on your control system, reach out to us or checkout our blog on Preparing for an Assessment of your Industrial Control System.

Learn more about DMC's Industrial Networking and Cybersecurity expertise and contact us for your next project.